With every opera comes a rich set of stories, and our very-fast-approaching season of Giuseppe Verdi’s Rigoletto is absolutely no exception. And so with that in mind, nau mai haere mai to a brand new season of Stage Notes!

In this series we go deep inside and behind the scenes of our stunning productions, giving extra insight to the massive work underpinning the magical experience that is a New Zealand Opera season. Keep an eye out for upcoming instalments, and thank you for having us in your inbox – we can’t wait to return the favour at our season of Rigoletto!

“The major Italian musical dramatist of the nineteenth century”

That’s how the English National Opera describes Giuseppe Verdi. And, certainly, it’s a sentiment echoed widely: the New Penguin Opera Guide calls him “one of a tiny group of composers who set the supreme standards by which the art of opera is judged”, while the New Kobbe’s Opera Book states that through the second half of the 1800s, he “dominated opera even more than Rossini had in the first”.

In a way, his work as a composer of opera – titles like Macbeth, La traviata, Il trovatore and, of course, Rigoletto – speaks for itself. But Giuseppe Verdi was an enormously fascinating character in his own right; one whose backstory adds crucial context to the work he would go on to create – and the sensibilities he’d so often strike against.

Born in 1813 in the tiny village of Le Roncole, Parma (now named Roncole Verdi in his honour), Giuseppe Verdi was a country boy who undertook musical training from a young age, becoming the local church organist at the age of 8. With his prodigious talents quickly becoming regionally known, a local merchant by the name of Antonio Barezzi from the larger town of Busseto took the young Verdi under his wing; welcoming him into his home, paying for his studies in Milan, and in 1836 becoming his father-in-law.

After living for a time in Busseto, Verdi and his now-wife Margherita eventually returned to Milan for the premiere of his first opera, 1939’s Oberto, at that city’s La Scala theatre. The work would make waves, and its composer would soon find himself in high demand.

A genius in his ascendency, or descending into obscenity?

Verdi was prolific through the first part of his career as a composer, writing 15 operas between that Milan debut and the premiere of Rigoletto at Venice’s La Fenice. In an essay commissioned for the programme of our 2012 Rigoletto season, Verdi scholar (and former director of the New Zealand School of Music) Elizabeth Hudson noted that while the years preceding its premiere had seen Verdi acquire a reputation as an artist of rare skill and range, his 16th opera was a “major turning point” for the composer.

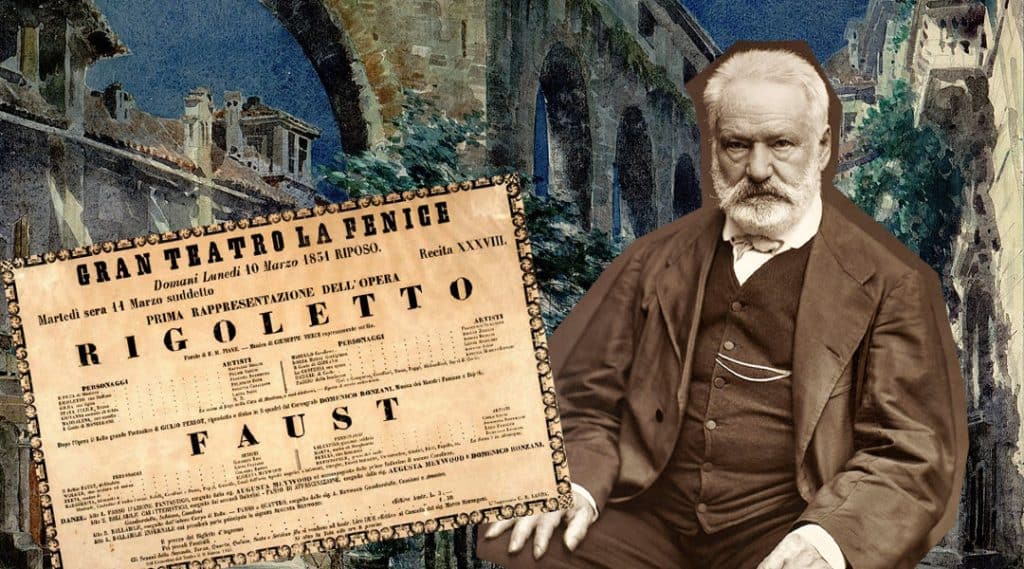

But although it would eventually be hailed as one of Verdi’s best, in its early days Rigoletto drew considerable controversy. Written after Victor Hugo’s Le roi s’amuse, a play notoriously banned after just one performance for its perceived anti-monarchist bent, the work of Verdi (and frequent collaborator Francesco Maria Piave) likewise attracted censorial attention.

Citing the “repellent immorality and obscene triviality” of Piave’s libretto (and, according to Penguin, going so far as to express regret that “the ‘celebrated maestro’ had squandered their talents” on such material), local police imposed a ban on its performance in Venice before it even had a chance to open.

After some furious rewriting on the part of Piave – and some just-as-furious protests on the part of Verdi – the work was eventually deemed to be sufficiently respectful to the ruling class, and allowed to premiere in March of 1851. It wouldn’t take long for its reputation to take hold, and within 10 years the work had been performed in more than 250 opera houses; in the time since, its status has only grown.

Enduring beauty, indisputable power, and an indelible cultural footprint

Few aria have reached the cross-cultural status as the one which has become Rigoletto’s calling card, the snarky and sardonic third-act opener ‘La donna è mobile’. But while that ode to what our title character perceives as the innate ‘fickleness’ of women (supposedly inspired by a note once scratched into a window frame by French King Francios I, the target of Hugo’s original satire) has long since transcended its original context, this opera is by no means a one-hit-wonder.

Gilda’s first-act aria ‘Caro nome’ is widely held as among Verdi’s best, a subtly complex piece described in the New Grove Book of Operas as “delicately distinctive” and as signifying a clear break from “the ‘open’-structured ornamental arias of the previous [operatic] generation”. Maybe finest of all – and certainly in the opinion of Verdi himself – is the famous third-act quartet ‘Bella figlia dell’amore’; described aptly by the Metropolitan Opera as a “masterful quartet that is an intricate musical depiction of four personalities and their overlapping agendas”.

But even more than that, the quartet is the beautiful embodiment of a singular strength of opera as an artform: that it allows multiple distinct characters to simultaneously – yet independently – express themselves through emotion and language. Victor Hugo certainly thought so – as local opera historian, the late Nicholas Tarling wrote in a piece for our 2004 programme, Hugo had initially been affronted at the idea of his work being “demoted to a mere libretto” and in fact tried to present Rigoletto from being staged at Paris’ Theater Italien.

Unsuccessful in his efforts, Hugo was eventually persuaded to attend the opera and found himself taken aback by the quartet in particular: “Superb, marvellous, incredible!” he enthused, going on to note (surely with tongue just barely in cheek): “Of course, if in my plays I could make four characters speak at the same time and have the audience grasp the words and the sentiments, I too would have the very same effect.”

Witnessing that climactic moment, when the voices of Gilda, Rigoletto, the Duke of Mantua and Maddalena converge – some in dialogue with each other, some expressing their innermost feelings to themselves alone – it becomes immediately clear that for all which has been written about Rigoletto, and for as well-known as some of its music may be, this is a work which has lost none of its power or potency. And so whether you’re intimately familiar with that source material, or have never before been exposed to a Verdi opera, we trust that this season will leave you entirely satisfied.

That’s all for now, but keep an eye out for our next instalment, looking into the history of this season’s legendarily gorgeous Elijah Moshinsky staging.