Kia ora koutou and nau mai haere mai to the first instalment of Stage Notes for New Zealand Opera’s highly anticipated 2025 season of La bohème.

For those who enjoy opera, few pursuits draw more reliable pleasure than engaging in impassioned debate about which works make up the artform’s true canon. But even in this most contentious of conversations consensus can occasionally be found – and you’d go a long way to find an opera lover who wouldn’t put La bohème somewhere close to the top of their list.

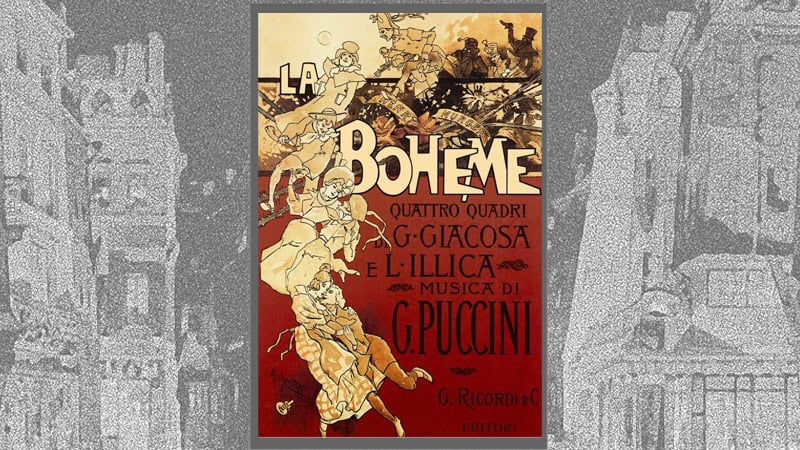

As we prepare for the return to New Zealand stages of Giacomo Puccini’s rumination on life, love and heartbreak in Bohemian Paris – opening in Tāmaki Makaurau in just three weeks – we thought now was the perfect time to dive a little into the history of this wonderful opera, and to examine exactly what makes it one of the most beloved works of all time.

Scènes de la vie de bohème

As with many great operas, the origin story here is a somewhat knotty one. Based on a loosely autofictional collection of vignettes, published as a novel (and subsequently written in abridged form for the stage) in the mid 19th century by French writer Henri Murger, La bohème was the fourth opera in Puccini’s still relatively young career – completed in 1894, it’s widely considered the first work of the Italian master’s ‘middle’ period.

But while Puccini’s bohème would go on to become a consensus canon work, he wasn’t the only notable Italian to make an attempt on Murger’s source material. In the midstages of Puccini’s composition process, a dispute arose between he and Ruggero Leoncavallo (Pagliacci), who contended that he’d earlier presented a completed libretto for the opera to Puccini – and as such, that his work should take precedence. Puccini naturally disagreed, countering that his work had already been in progress for some time prior to Leoncavallo’s intercedence* and defiantly suggesting, “Let him compose, I will compose. The audience will decide.”

And to grossly oversimplify things, that’s basically what happened. Both men would eventually publish and perform their own takes on Scènes de la vie de bohème, with Leoncavallo’s effort premiering a year after his rival’s and eventually being seen as little more than a footnote in his career as a composer. Puccini’s version, however, would go on to achieve a quite different status.

*Later scholarship would reveal that Leoncavallo probably wasn’t lying about the timeline here. Unfortunately for him, by the time anyone figured this out, Puccini’s work was well and truly established as the definitive La bohème adaptation.

A growing reputation

With a story so perfectly formed and a score so sumptuous the rise of La bohème in the canon likely came as no surprise to those lucky enough to see it in its early showings. Looking back, though, the pace of the opera’s rise appears almost unbelievable. Premiering at Turin’s Teatro Regio in the winter of early 1896, by the end of that year the opera had already been mounted by a further three companies across Italy – as well as Argentina’s Teatro Colón – and by the end of the century, with performances in Lisbon, Moscow, London, Berlin, New York, Los Angeles, Paris and Prague, its status was cemented across the globe.

Since that point, it’s a status which has only grown – according to statistics produced by online platform Operabase, La bohème was the 4th-most performed opera of the 2010s, with close to 7,500 performances across more than 1,500 different productions. More than that, its footprint extends well beyond the proscenium arch, too – both the Tony-winning musical Rent and the Oscar-winning film Moulin Rouge found enormous success in lifting liberally from Puccini’s work; the tale of artists in deep, doomed love truly as adaptable as it is ageless.

But what of the music?

Puccini is widely held – alongside contemporaries like Pietro Mascagni and the aforementioned Leoncavallo – as a leading proponent of the ‘verismo’ tradition; a less fantastical, more grounded counterpoint to the fanciful subject matter often associated with the bel canto style. But while the slice-of-life drama sung through La bohème may shy away from gymnastic vocal flourishes, it’s by no means any less arresting.

From the stunning pair of arias that mark Rodolfo and Mimi’s first meeting – his ‘Che gelida manina’ (‘What a cold little hand’) followed by her gorgeous ‘Sì, mi chiamano Mimì’(‘Yes, they call me Mìmi’) – to Musetta’s showstopping turn in act two, ‘Quando m’en vo’ (or ‘Musetta’s Waltz’, as it’s often called), among these four acts sit some of the most recognisable, most undeniably beautiful pieces in the entire operatic repertoire. And with a world-class selection of local and international singers making up our cast for this production, alongside the outstanding Freemasons Foundation New Zealand Opera Chorus and the finest orchestras in Aotearoa, this season of La bohème will showcase Puccini’s endlessly enduring work at its absolute best.